|

The reaction of football clubs to events such as that at Manchester United last week reveal something vital about the psyche of the football clubs. They are communities, comprised of players, staff, stalwarts and supporters, regular and intermittent; and even if they are not representative of the localities in which they are based, that base remains an essential part of their root structure and individual identity. They share - or at least they should - the sporting values of aspiration and competition and respect for fellow competitors.

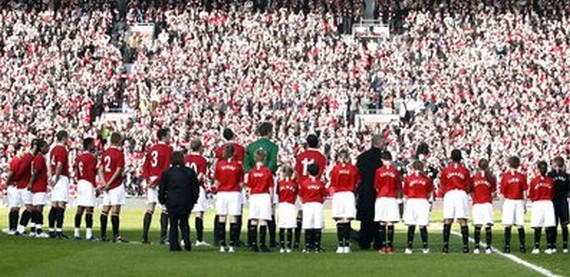

Manchester United revered that week their own sporting heroes, young men of their community who were fine ambassadors for that club and who by their untimely death became the subject of a grief which became part of its identity.

How ironic and distasteful then, that barely 24 hours later, the powerbrokers of the league of which Manchester United are the single most dominant entity casually dropped in their latest bombshell. Thankfully, subsequent reactions have restored some faith that there remains an overwhelming body of opinion which has a proper sense of perspective of what it is to be part of a sporting culture. But that it has come to this point at all is indicative of how far football has drifted from that rightful identity.

This notion of an extra, incongruous game on alien soil has raised so much opposition because it is intuitively more than wrong. Not because - as the FA have appeared to suggest in an alarming and spectacular demonstration of missing a point in its totality - it would increase the demands on players. This is one of those occasions when the quality of the product, the ability of players to perform, is entirely sub-ordinate to the fact an idea is an affront to everything a sport should be about.

Sporting competitions have always, since time immemorial, been held with one overriding object: to find the best; the most powerful, the most skilful. The format which William McGregor formulated almost exactly 120 years ago, with symmetrical home and away fixtures, remains its purest. One extra game, drawn at random can never be insignificant. It is an extra three points and as everyone with a football soul knows, that can have a disproportionate importance in the final analysis.

Yet even that is not as utterly abhorrent as the idea that clubs should cast themselves adrift of their moorings in order to set off around the world. The result of the values and that identity which Manchester United acknowledged and celebrated is that every club has its home.

Any individual has the right to attach their loyalty to any football club they choose, but they have no right to demand where it plays its games, because that is integral to the heart of the club and you cannot pick and choose which bits of that heart you adopt and which you discard. Live in China? If the connection is strong enough, make the pilgrimage. If not, tough; find your sporting passion closer to home.

And so it was soul-destroying to hear as intelligent and sensitive a man as Arsene Wenger arguing that it is only fair to give far flung, television supporters an opportunity to watch a live, competitive game. Fairness? Great. Coming soon: the 40th game, with free access to every supporter who cannot normally afford access to a Premier League Game. Welcome to the caring, sharing Premier League, where neither geography nor financial means are a barrier to participation.

But if the idea provokes anger, then it ought to provoke sadness in even greater proportions, because this is an inevitable, logical conclusion of every shift in the dynamic of football since the mid 1980s. And although Richard Scudamore might be a nausea-inducing individual, the truth is he is a man with a job to do, and he cannot be blamed for attempting to do it to the best of his ability. Somebody has to.

|

The same ruthless logic applies to those clubs like Liverpool and Manchester United, owned privately by individuals and consortiums whose eyes are firmly fixed on the bottom line. And these owners aren't the custodians who once involved themselves with their local club. They are global businessmen, based in America, Hong Kong, China and Thailand - indeed, precisely the countries identified in the Premier League's export plan.

I, like thousands of football fans, make my daily living within the modern commercial jungle. I'm not criticising that culture in itself. But the rules which apply to my everyday existence - I don't want them to apply to football. I want football, sport in general, to be different. I want it to be an alternative world of different, less cut-throat values, where the real object is the love of the game itself rather than consuming every single competitor.

My anger, then, is directed away from Scudamore and the club executives to whom he is answerable. It is aimed at those who have the power to intervene at a higher level, yet who, on every occasion that the integrity of the game is challenged, stand aside, wringing their hands and squealing mutedly.

The Football Association has fudged its response to this issue, just like it has on every occasion that it has been challenged over 20 years. Perhaps the monster that the FA and its Premier League created has now grown too big for the FA in its current form to ever control. The FA has always been more or less a self-regulatory body and the top-flight clubs, left to their own devices, have ably demonstrated time and again that, when given a penny, they will steal a thousand pounds.

Having reached that point of no return, we cannot simply continue to shoehorn football into the framework of laws which are not designed for its unique purpose. Governments have turned away from football for too many years, but there must be an acceptance that sport is different, and football clubs must be restrained from disregarding and disrespecting its social and competitive fabric. How that should be done is too big a topic for this moment. The clock cannot be turned back, but order can be restored for the future.

Moreover, the government regulates, whether via statutory agencies or ombudsmen and watchdogs, almost every other industry which is considered to have a social responsibility. That a multi-million pound industry such as football continues to escape such regulation is utterly incomprehensible.

It is a long time since the members of the English Premier League decided that, rather than celebrating and respecting football clubs beyond the confines of their transient, breakaway collective, they would attempt to consume them. They are now simply seeking to apply that same attitude to the rest of the world. No-one within football is ultimately capable of restraining that raging motivation.

But that means the task must fall to elsewhere. Otherwise, football's march of progress will continue, inexorably, to transport the game a million miles away from spirit and soul of the game played by the Busby Babes, half a long century ago.