|

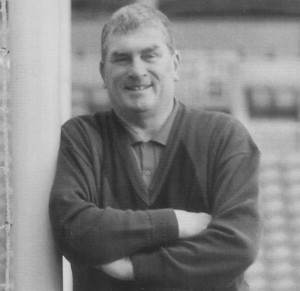

Tributes have already appeared on this site from Tony Scholes and Dave Thomas, both of whom were fortunate enough to have seen his multi-faceted contribution to the club at close quarters, and to have known the man personally. I can claim neither. I belong to a more recent generation of Clarets whose view of Brian Miller is more detached, fuelled by what we are told by others and by the reverence held by our elders. By the time I started watching Burnley he had stepped into the shadows and turned his tutored eye to uncovering talent as chief scout. Yet I know his name, and I know his story. We all do.

And it is a fine tale of a phenomenal yet understated life. It is hard to imagine that another figure in the professional English game has ever experienced the oscillations in emotions - from the highest peaks to the deepest troughs - that Brian encountered along his journey. If there is, then there is no-one else who did so with just one club.

Burnley's is a unique history of highs and lows. It has always struck me as a story which might one day make a decent script: the small town club, the pride of a working class town, who took on the bigger clubs of the establishment and won the title, went to Wembley and ventured into Europe - yet which then fell into a seemingly irreversible decline, from the very bottom to the very top, from a small fish in the biggest pond to one of the biggest in the smallest, maligned and ignored by that town as gates dwindled to nothing.

It is a story of triumph and near disaster built around two defining moments - the Championship of 1960 and then Orient. And at the heart of that tale would have to be the man who was at the heart of both, and who was there at every twist and turn in between. The Boys Own tale of a local lad who rose to play a pivotal role in that Championship win and who went onto play for England (remember that, although Gawthorpe was producing talent on an industrial scale, the overwhelming majority of it came from outside the borough) would in itself be sufficient to warrant a mention, without the chapters of devotion and commitment which followed, and without the ultimate responsibility for steering the club to redemption which fell upon him.

Older fans will probably wish to remember Brian Miller firstly as a player of distinction, and as the manager in 1987 secondly at best. Perhaps that is right; for it almost seems unfair that he should be associated in any way with the worst team in the club's history. But for supporters of my generation, he is probably remembered primarily as the manager who guided the team to safety almost exactly a month short of 20 years ago.

It is a good job that Brian Miller did accept the task when the club came calling, for had he invited the club to look elsewhere for a leader through that desperate campaign, it could have turned out unimaginably worse. Had he done so, he could hardly have been blamed. Yet I suspect that the club knew his answer before they asked the question: I imagine that they knew that he could never have turned his back on a club which was so deeply ingrained within him.

And yet, when he took the job, he knew he faced being the man people associated with the demise of a club about which he himself cared so passionately. He might have been carrying the can for other people's mistakes - there isn't a single person with whom I've ever spoken who has suggested that his role in that season did anything but improve Burnley's chances of survival - but that isn't the point. He risked being the last league manager Burnley ever had.

Therein lies the essence of what the wider football community should be reflecting upon. For this is the kind of man who is absent in the game today, where even the one-club player is an almost extinct concept, and the idea of a one-club life is inconceivable. The kind of man for whom football was a vocation, not a lifestyle or even just a job. A man who entered the spotlight only with reluctance, but who when he had to do so to shield others, did it with a quiet dignity and determination.

I know I'm not alone in viewing Burnley's post-war history from a different perspective to older generations. Those who had the privilege of being there in the 60's and then the 70's start with that, and work towards the gathering clouds of 1987. For my generation, I think it is other way round. I think we start with Orient, and work backwards, towards the glory years, because without Orient, we wouldn't have a club to attach it to.

The reason that history and the people who made it mean something to me, the reason that I think that story is so special, is because there is a present upon which to hang that history. My father would, even had Burnley lost to Orient, have been able to tell my sister and me all about it, but he wouldn't have been able to make us a part of it. It would have remained only a good story, without the personal involvement which gives it such a deeper importance.

I don't suppose Brian Miller would be too bothered that the national press failed to mark his passing. It would probably strike him that a man associated with Burnley Football Club was usually below the radar - except, of course, on that day in 1987. And it doesn't really matter anyway. Turf Moor stood as one on Monday afternoon, young and old alike, in perfect silence. The older could cherish their memories of a fine player and manager, and the younger of us could reflect that, in some large part, we owed our identity as Burnley supporters to the man being honoured.

There are many who can say that they left a legacy at a football club. Great players, characters and toilers who shape the history of a football club. But perhaps Brian Miller's was the ultimate. Arguably, it was the club itself.