There was Philip Brown, Ed Cockcroft, Jammy Fielden, Winston Sutcliffe, Colin Walker, and a whole host of other lads like us who tore up and down in mud, rain, hail and on some days, snow. But one thing was always constant. One of us would always be Ray Pointer, one of us would always be Jimmy Mac, and one of us would always be John Connelly. It was just those three; nobody bothered about being Brian Miller or Jimmy Adamson, great players though they were, but the other three were always represented every Friday afternoon.

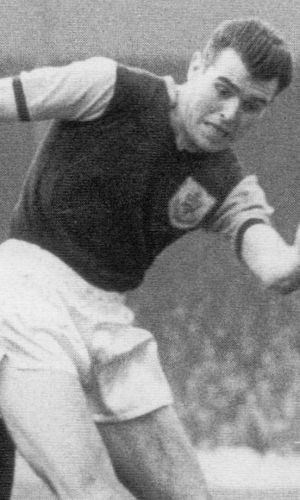

Somehow John Connelly was always ‘hip’. It must have been his hair, that luxuriant combed back thick hair and that good looking almost boyish face that was the appeal, plus of course his fabulous goal scoring ability. There was almost a touch of the Elvis about him. We give hero status to any centre forward these days who scores 20 in a season. He was a winger and scored 20. One of them still sticks in the mind when he cut in from the right wing and unleashed a 20-yard thunderbolt that was in the Spurs net before you could blink in a 2–0 win in ‘59/60. For good measure in that game he provided the rocket cross from which Pointer scored an equally bullet header. He was a totally class act.

Somehow John Connelly was always ‘hip’. It must have been his hair, that luxuriant combed back thick hair and that good looking almost boyish face that was the appeal, plus of course his fabulous goal scoring ability. There was almost a touch of the Elvis about him. We give hero status to any centre forward these days who scores 20 in a season. He was a winger and scored 20. One of them still sticks in the mind when he cut in from the right wing and unleashed a 20-yard thunderbolt that was in the Spurs net before you could blink in a 2–0 win in ‘59/60. For good measure in that game he provided the rocket cross from which Pointer scored an equally bullet header. He was a totally class act.

Maybe the goal he will always be remembered for is the one at Reims in the European Cup. Burnley had won the first leg 2–0 at Turf Moor but it was his stunning goal in the second game that clinched the tie. Years later he vividly described it in an interview I did with him.

Fame and glory meant little to him when he finished playing. He had been a great footballer, an England international, a key member of the Man Utd side, but it was all over and done with. Bobby Charlton devoted four pages to him in his autobiography. He said he was strong-minded and one of the few players ever to stand up to Sir Alf Ramsey and was one of the few players ever at United to stand up for a better salary.

He was a vital player in their title team, he wrote; he and Best complementing each other on the flanks. Connelly was able to make his presence felt and ‘elected himself to a tough group of survivors that included Terry Paine of Southampton and Johnny Morrissey of Everton. It was a small group of talented wingers who had learned that in an increasingly physical game they could not afford just to take the knocks, brush themselves down and return to the action.

In my view though, Connelly was the best in this category. He wasn’t afraid of leaving his foot in; it produced instant respect in any marker’. He was perfectly equipped for the survival game. He was strong and quick and I rarely saw a winger who was happier to take on the challenge of unnerving a full-back. If he had a chance to move on goal he was not reluctant to do so. His greatest contribution however was to get to the bye-line and cross accurately. John had a spiky quality, and like Johnny Giles he was to learn that the voice and judgement of Matt Busby was not wisely questioned if you wanted to make the United experience a long one.’

Charlton goes on to say how when he was in East Lancashire he would make a point of trying to visit ‘Connelly’s Plaice’ chip shop. ‘As a magistrate he was not afraid of administering tough justice, and he would tell me how some of his regulars would come in the shop and complain if John and his colleagues had found them guilty and given them a stiff fine’.

John would have been a happy man to know that he had the ultimate respect of Bobby Charlton. ‘He was known for what he was at Old Trafford: a tough professional who always came to work with a most serious intent. Defenders knew what they were getting when they faced Connelly’.

I interviewed John in 2008 for the second volume of No Nay Never. It was a morning that sped by and the result was this:

‘To say that John Connelly is a modest man who likes a quiet life is an understatement. Today, he avoids the limelight. He is happy to play golf and take time away from home in his touring motor home and for many years he ran a successful fish and chip shop in Brierfield. All the Burnley players of yesteryear I have met have always come across as just the ‘bloke next door’ and John Connelly is no exception.

When I met him at his home near Barrowford, of course the marvellous solo goal he scored at Reims was mentioned … but by me not John. The morning flew by and I doubt we touched on a fraction of the stories he has to tell. When you have played with people like Best, Law and Charlton at Old Trafford, and all the great names who were his World Cup colleagues in 1966; when you have been in the game for as long as he has, for sure you have a tale or two to tell. As a result he has been offered money to tell the kind of stories that ‘reveal all’ but he has no interest in that, or any kind of controversy.

Like most, if not all of his generation, John Connelly made no great fortune from the game and had to work for a living afterwards for many years. Even as a young player he had a ‘daytime’ job, working as a joiner for the National Coal Board instead of National Service. Training was after work or in the evenings. It’s hard to imagine that kind of routine now.

He was one of that fledgling group of young players signed by Alan Brown, when he joined from St Helen’s Town. He recalls the occasion when he signed and the imposing Alan Brown sent for him.

‘Put some kit on’, he was told. He obeyed and there in the dressing room was a photographer to record the event. ‘Now get your clothes on and come with me’, was the next command. Off they went to the station and Brown disappeared into the left-luggage office and then came out with a battered old suitcase, the shabbiest you could imagine. He gave it to Connelly. Then he handed him the grubbiest old raincoat you could imagine. ‘Put that on’, he was told. Connelly did as he was told. The photographer was there again and proceeded to take pictures of him with the tatty suitcase, standing by a steam train on the platform.

‘John Connelly arrives to sign for Burnley’, he thinks was the caption.

‘And my mother was mad as hell when she saw that picture’, Connelly laughed. ‘She thought I looked like a refugee’.

Not only did Connelly pose in a shabby old raincoat because he had been told to do so, he also signed a blank contract because he was told to do that as well. ‘Just put your name on that and we’ll do all the rest,’ said Brown.

It was in his debut game that he saw how Brown could go ballistic when he was angry. But this was anger at the state of Connelly’s legs when he saw how many stitches he would need in a leg wound after his initiation into the world of over the top tackles and intimidation.

Before he joined Burnley, Connelly used to watch Everton one week and Liverpool the next. Billy Liddell was his idol and on meeting him years later at a charity event he remembers he was awestruck. He also remembers watching Harry Potts play when he was at Everton.

“Great diver,” he recalled, grinning.

“I just loved playing,” he said with another smile. He smiles a lot. Bearing in mind he was a winger who could score goals, and not particularly physically robust in his early days; he did well to avoid serious bodily harm in what was quite frankly a brutal age.

“I scored goals and that meant going in where it hurt. Probably the hardest opponent I faced was a chap called Don Megson from Sheffield Wednesday. When he walloped you, you knew about it. Bolton Wanderers had a big side and they had Tommy Banks at full-back. He was hard but I was lucky; he was just ending his career as I was starting. He was never fast and when I played against him he was even slower. Mind you, there was one game when I thought I’d switch wings with Brian Pilkington to get away from him. Then I looked across and saw who it was on the other side. It was Roy Hartle. So I stayed where I was. In those days you knew you were going to get wellied if the opponents got the chance but you just got up and got on with it. And the boots we wore back then were like concrete. They were so stiff and you had to break them in and wear them a few times at Gawthorpe to soften them before you could ever wear them for 90 minutes in a game. And we didn’t get a new pair every two weeks from sponsors. They were repaired over and over again at Cockers in Burnley.”

|

| Bob Lord provided John & Sandra's wedding car |

I mentioned the legendary Cup game in the mud at Bradford City in the early 60s. It’s a shame there is no archive film of this game to show people just what the conditions were like. John claimed both goals, scored in the last five minutes, the goals that salvaged a draw. The mud was so deep, the pitch was so bad that not a spectator was able to say with confidence exactly who scored as they slithered around in this thick oozing stuff covered from head to foot in it, their faces completely obliterated. All of them were totally unrecognisable.

“Sandra and her family were there to watch. I was only courting then. After the game I asked Harry if I could go home with them instead of on the team bus. To this day I can remember Harry’s beaming face and him telling me I could go wherever I wanted. I actually lost a boot in the mud. It just sucked it off and when I found it, it was half buried in the stuff. “

The mention of Sandra reminded him of a Bob Lord story. “He was a wonderful man who would do anything for his players and he looked after us well financially. When I got married in 1960 I’d arranged to hire a car and was supposed to collect it the day before the wedding. Then the hire firm decided I couldn’t have it. It was in the summer and Harry Potts was away on holiday so I phoned Bob Lord for help. I went to see him at his Lowerhouse factory. There he was in his white coat and cap.

‘What can I do for you?’ he asked.

“I explained about the wedding, the car and the honeymoon. ‘Well, what do you want me for?’ he said gruffly.

“Well,” I said. ‘If you can’t help me nobody can.’ That was exactly the kind of thing he liked to hear. People who made demands got nowhere. You had to set him a challenge. ‘Tell your lass not to worry. There’ll be a car for you if you come down the day before you marry’, he said.

“So down I went as instructed and there was the biggest Wolseley you’ve ever seen. I thought I’ll never drive that it’s so enormous. Anyway I did and we went down to Newquay for the honeymoon thanks to Bob Lord. I think it took about two days to drive it there. There’s so much that he did for people that no-one knows about.”

Part 2 of this interview will follow on Monday 5th November, the day of John Connelly's funeral.